- No single system will operate in isolation anymore – at least that is the ambition of militaries going forward

- Repeated drone incursions have prompted suppliers to combine their products into one versatile and mobile platform

- Atlantic Bastion has opened the door to an emerging niche in the underwater systems sector centred around disaggregated sensors

There are glaring areas of concern that require immediate attention in 2026 beyond longer-term projects that have come to dominate discussion in defence such as directed energy lasers, hypersonic missiles, or sixth generation fighters to name a few.

While these capabilities still play a decisive role in modernising combat capabilities over the next several years, these projects are far less pressing than some strategic priorities that have unravelled this past year.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

The need for new open system architectures, the ability to protect against an uptick in adversarial drone incursions, and the vulnerability of subsea infrastructure each represent an immediate capability gap which adversaries, particularly Russia, are actively exploiting today.

Digital integration

No single system will operate in isolation anymore – at least that is the ambition of militaries going forward.

This vision links all systems together, with relevant data being collected and passed along a network of interconnected nodes, and all of this is sped up by artificial intelligence.

The UK government, for one, plans to construct a Digital Targeting Web by 2027. This ambitious task will be underpinned, in whole or in part, by a Defence-wide Secret Cloud with a minimum viable product available in 2026.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataSome steps have already been made to achieve this as the Ministry of Defence signed a £400m contract in September to share defence intelligence with the United States using the Google Cloud platform.

For now, though, the British Army are currently testing different networks to augment its Recce Strike approach under Project ASGARD. One of these is Anduril’s decentralised Lattice mesh network, which a company representative demonstrated to this reporter in a simulation using a virtual reality headset in September.

Simulating an operational scenario, the Lattice system integrated various platforms and sensor nodes together and enabled the UK military requirement for crewed-uncrewed teaming.

Elsewhere, the US military announced in November that it would incorporate Lattice as a fire control platform against swarms of small uncrewed aerial systems (UAS) as part of the Army’s wider IBCS-M programme.

However digital integration is also happening at the strategic level too. The US defence contractor Northrop Grumman is delivering its Integrated Battle Command System (IBCS) for the US and Polish armed forces.

This system, in contrast to the tactical autonomy of Lattice, coordinates sensors, deciders and effectors for joint all-domain command and control, with a focus on integrated air missile defence at the batallion level or higher. It operates on an “any-sensor, best weapon” principle.

C-UAS

A new demand signal has emerged across every layer of air defence as the world watched Russian airspace violations rise this past year.

In particular, Russian UAS have tested Nato’s resolve, crashing into homes in Poland to shutting down an airport in Denmark, the drone threat has left Europe scratching their heads in consternation.

“Legacy air defence systems were designed for fast, scarce and high-value targets” said Jan-Hendrik Boelens, the CEO of Alpine Eagle, responding to Army Technology. “Drones are the opposite: slow, cheap, numerous and disposable.”

Alpine Eagle is a German supplier that offers the Sentinel C-UAS system used to detect, classify, and intercept UAS in the air.

The counter-drone (C-UAS) problem has seen a cost gap between cheap attack drones and the legacy, multimillion dollar air defence systems and the missiles used to intercept them. This has prompted substantial growth in the missile defence sector over the next ten years, reported the intelligence firm GlobalData, which says investment will increase from $55.7bn to $98.5bn.

“The focus is shifting toward autonomous, software-defined systems that can detect, track and engage drones earlier and at lower cost,” Boelens described.

This will bring together novel technologies from airborne sensing, artificial intelligence-driven classification, and mobile C-UAS platforms, all of which “are gaining traction because they remove terrain blind spots and compress reaction times,” he continued.

There is a trend in the global defence industry in which companies are pulling together to fill this capability gap by combining their individual products in an open architecture. Industrial cooperation was common during the AUSA 2025 exhibition in Washington. These joint initiatives were based around a single mobile platform carrying a number of effectors.

Honeywell, for example, tested two configurations for the US government at the time as a lead integrator. A sales representative told this reporter in October that the company explored the C-UAS and sensor markets to integrate various systems among different suppliers.

The first concept is said to have met all test parameters in a Ford Ranger driving up to 70 miles per hour, integrating radars, electronic warfare (EW) effectors, and electro-optical and infrared sensors on a pickup truck. The second added more radars and other acoustic and drone capture capabilities, including a system hung from a 13-foot aerostat.

“In 2026, the priority must be speed of adoption,” Boelens urged. “That means modernising procurement, integrating counter-drone measures as a core layer of defence and infrastructure protection, and backing systems that can deploy quickly, update continuously and operate at scale.”

While industry are playing their part well, government and the armed forces will need to step up next year to deliver that speed of adoption in a cultural sense. The military will need to confront a force structure problem: how to dissemniate short range air defence capabilities.

Currently the British Army only have two air defence regiments; this not nearly enough given the proliferating drone threat in Europe. Air defence has become an all-arms problem now.

Underwater systems

Another major strategic vulnerability is control over the Baltic, Atlantic and to a lesser extent the Pacific.

Not only does this concern the protection of critical subsea infrastructure but also sea denial against Russian naval assets in strategic chokepoints, such as the Greenland–Iceland–UK (GIUK) Gap and the Norwegian Sea, which the First Sea Lord, General Gwyn Jenkins, remarked on in his speech earlier this month.

Seeds have been sown to address the problems in the opaque domain, particularly concerning the North Atlantic. Foremost among them, the UK Strategic Defence Review conceived the Atlantic Bastion strategy, which envisions a layered network of uncrewed and autonomous systems, integrated with advanced sensors and traditional crewed anti-submarine warfare (ASW) assets such as the Type 26 frigate.

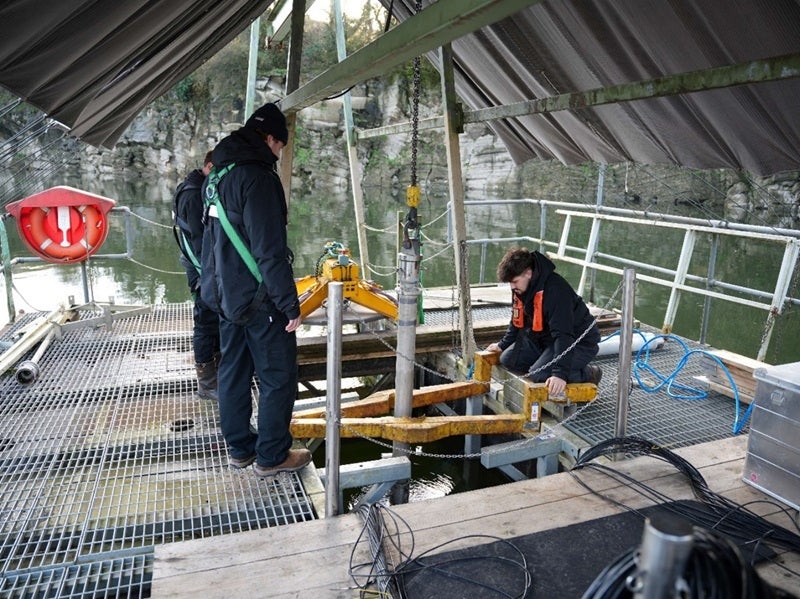

Atlantic Bastion has opened the door to an emerging niche in the underwater systems sector centred around individual disaggregated sensors as well as uncrewed underwater vehicles (UUV).

A Thales director recently told this reporter that their existing acoustic detection sensors currently in service with the Royal Navy were being “worked harder and worked more” which prompted the supplier to develop a smaller sonar suite for UUVs called Nano76, which the company anticipated to be a requirement prior to the release of Project CABOT.

Global partnerships have also formed to fill this creeping capability gap. The US defence contractor Anduril is working with British supplier Ultra Maritime, combining the Dive XLUUV with the Sea Spear array to detect submarines.

Likewise, Helsing unveiled its SG-1 Fathom autonomous underwater glider, enabled by a large acoustic model called Lura, to monitor the ocean for submarine noise. In some cases, the company claims the capability has been able to differentiate ships of the same class.

Upon closer inspection, however, some experts have argued that the focus on sensing and detection systems, which should only be one part of Atlantic Bastion, is too narrow a focus.

Royal United Services Institute fellows Dr Sidharth Kaushal and Commander Edward Black published a report on 16 December that suggested the concept must function “beyond a network of relatively low mobility sensors”. The authors noted the UK and Norway will need to have a credible offensive capability in the theatre: “the Bastion will have a more limited impact without strike being incorporated within the Bastion area”.

Nevertheless, the UK’s sensor fixation will continue to encourage a thriving market for subsea intelligence, surveillance and reconnaisance systems going into 2026.

Meanwhile, in the Pacific, the US Navy will similarly pivot to cultivating a larger ship count with a mix of comparatively smaller crewed vessels and autonomous maritime vehicles than the larger, more complicated and costly Constellation class frigates – a programme that has lately been cancelled.

This pivot marks a new force structure design, contrary to the “poor choices made decades ago”, noted the Chief of Naval Operations Daryl L. Caudle in July. Going forward, the Navy will be “massing effects from multiple vectors, platforms and environments” he envisioned. This feeds into a new naval strategy that values the effect of a capability integrated within a wider digital network.